As we talked about in Part One and Part Two, there are an endless number of options available to build an AR style firearm build. Once you start to define what the firearm will be used for, it starts to narrow down the choices. For this post, we will mostly be discussing AR-15s in .223 Remington/5.56 NATO, because different calibers could require a different thought process in choosing the right barrel length and gas system length.

To start with, there are AR-15 pistols, and AR-15 rifles, which operate in similar ways, but have distinct differences in characteristics defined by law. We are not lawyers, but to paraphrase some of the general distinctions, in the USA a rifle must have barrel length greater than 16 inches, and is equipped with a stock that is designed to be fired from the shoulder. Pistols are not designed to be fired from the shoulder, and generally have barrels shorter than 16 inches. There is also the classification of “short barreled rifles” (SBRs), that are rifles with barrels less than 16 inches, but those are National Firearms Act (NFA) firearms requiring additional paperwork and a $200 tax stamp to own, along with other restrictions we will not cover here. Do not put a shoulder stock on an AR-15 pistol with less than a 16″ barrel, as doing so violates the NFA, and can carry severe legal repercussions. In order to get some clarity on what firearms configurations are legal where you live, you should consult with a local attorney versed in firearms laws. We will explore some of the options between AR pistols and AR rifles in a future post, but for this post, we will focus on options for AR-15 rifles.

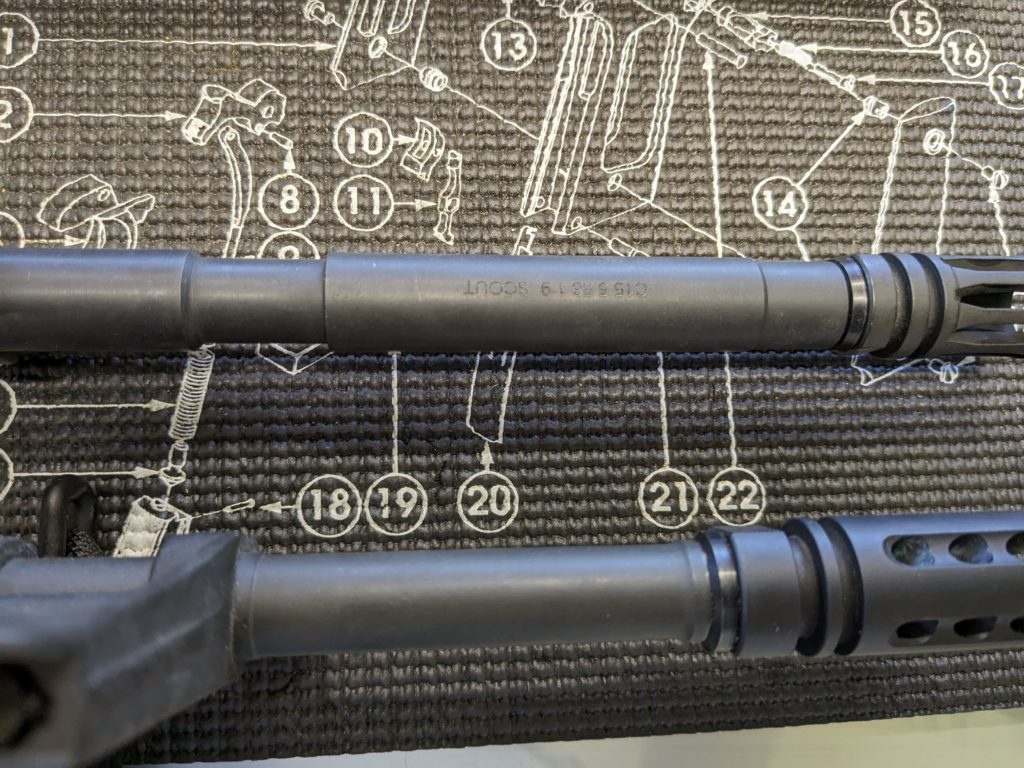

Barrel lengths for AR-15s are relatively standardized. The common options you will see for AR-15 rifles are 13.7″, 14.5″, 16″ 18″, and 20″. The typical barrel lengths refer to the length of the actual barrel, and generally do not include the length of the muzzle device on the firearm. This may sound contradictory to the paragraph above, but there are ways you can permanently affix a muzzle device to a barrel to get over the minimum 16 inch length. Doing so can get the barrel length over the minimum of 16 inches, and help reduce the overall length (OAL) of the firearm, as long as it is still over the minimum required 26″ OAL for the firearm. One such method is referred to as a “pin & weld”, which we will cover the pros and cons of in a future video. But, for instance a 14.5″ barrel with a permanently affixed 1.7″ muzzle device will be 16.2″ inches in overall length, and so it can be a normal rifle barrel. It is important to note that there is also a specific way the ATF requires barrels to be measured, so that procedure must be followed to verify a barrel meets the minimum required length. For example, the 14.5″ rifle in this post’s pictures has a total length of the barrel & permanently affixed muzzle device of 16.5″, and the 16″ rifle’s barrel with an A2 birdcage style flash hider attached is 17.5″. So, having the permanently attached muzzle device saves an inch of OAL for the rifle

So, why might someone want a shorter or longer barrel for an AR-15? A shorter barrel will be more easily maneuverable, and generally weigh less than a longer barrel. There are two main ways to reduce the weight of the rifle via the barrel, barrel length and barrel contour. There are also a common number of barrel contours, based on the outer diameter of the barrel, with obviously a thinner barrel weighing less. However, a thinner barrel will also heat up more quickly during firing, which can cause accuracy to degrade. A heavier barrel will heat up more slowly during firing, which can lead to greater consistency and therefor accuracy, and will also help to reduce felt recoil due to the increased weight. There are pros and cons to every single decision that is made during this process, so it is about finding the best balance to meet your needs, and part of why there are so many variations to choose from. This is why defining what the rifle is for is so important. Here we start balancing maneuverability of the rifle, vs accuracy and recoil impulse, both of which can be very important characteristics.

For a home defense rifle, a shorter barrel will likely be desirable since engagement ranges will be shorter, and it would be easier to maneuver inside a home. However, for a hunting or competition rifle, a longer barrel may be more desirable for increased accuracy, and reduced recoil impulse. On the US market for 5.56 rifles, 16″ barrels are the most common, but other barrel lengths can be found without much difficulty. Sixteen inch barrels are generally a good compromise of all the traits, and would be our general recommendation for a “jack of all trades” rifle.

The operating system on an AR-15 is a direct gas impingement system, in which some of the gas/pressure from a fired round is routed back into the bolt carrier group, allowing the firearm to work in a semi-automatic manner. Due to this, dwell time is an important concept to understand for properly setting up and tuning an AR-15. Dwell time can be thought of as the amount of time that the gasses from a fired round are able to interact with the operating system of the rifle. This is determined by the distance between the gas block, where the hole in the barrel allows gas to exit to operate the firearm, and muzzle of the firearm, because once the bullet exits the muzzle all pressure is released from the operating system. So the dwell time must be long enough for the gas to unlock the bolt carrier, and push it to the rear for extraction and ejection of the spent casing while also resetting the trigger, and generate enough force so that the returning bolt carrier group can chamber the next round from the magazine and lock the breech closed. However, more dwell time is not necessarily better, because that can caused increased wear on the operating system due to increased pressure.

There are a number of additional factors that effect dwell time, like buffer weight, or gas port aperture size, but for this post we will just focus on barrel length and gas system length. There are a number of common gas system length’s on the market, and some makers have their own proprietary lengths as well. However, the standard ones you will see for 5.56 rifles are carbine-length, mid-length, or rifle length. Often your barrel length will narrow down which gas systems will allow for a proper dwell time for your rifle. Shorter barrel lengths use shorter gas systems, with 14.5″ and 16″ barrels being either carbine length or mid-length gas systems. Longer barrel lengths, 18″ and 20″ are more often found in rifle length gas systems. If you are using a M-16 style combined gas block and front sight post, the gas system length will also dictate your handguard length, if you are using a low profile gas block, you have more potential choices in handguard length. Longer barrels and longer gas systems will allow for a longer sight radius, which can aid in accuracy if you are using iron sights. Longer handguards allow for more mounting space for accessories, and more potential places to grip the handguard.

Our baseline suggestion for most first time AR-15 purchasers is a rifle chambered in 5.56 with a 16″ barrel, and a mid length gas system with a low-profile gas block, and a handguard at least as long as the gas system. This is for a “jack of all trades” kind of build, that will be suitable for a wide variety of roles an AR-15 is commonly used for. If you want to talk about what sort of AR build will help meet your specific needs, we would be happy to have a conversation to guide you in the right direction, or to have the conversation and build a rifle to meet your needs.