As we talked about in part one, the intended purpose of an AR style firearm will help dictate the choices that need to be made in order to make the firearm suited to that role. One of the first decisions that needs to be drive is what caliber is ideal for the application, because that will influence a number of other decisions that need to be made. You may see different number designations after “AR” when looking at firearms, with some of the most common being AR-15, AR-10, AR-9, or AR-45. Each of these refers to a different format/size for the lower an upper receiver, and which one you need will depend on the caliber that you are going to use.

No matter what format and caliber you use, it is critically important to make sure you are using the proper ammunition for the firearm you are using. Don’t assume all AR-15s are one caliber, doing so can result in catastrophic failures and potential bodily harm. Make sure the ammunition you are using matches the roll marks on the barrel.

AR-15:

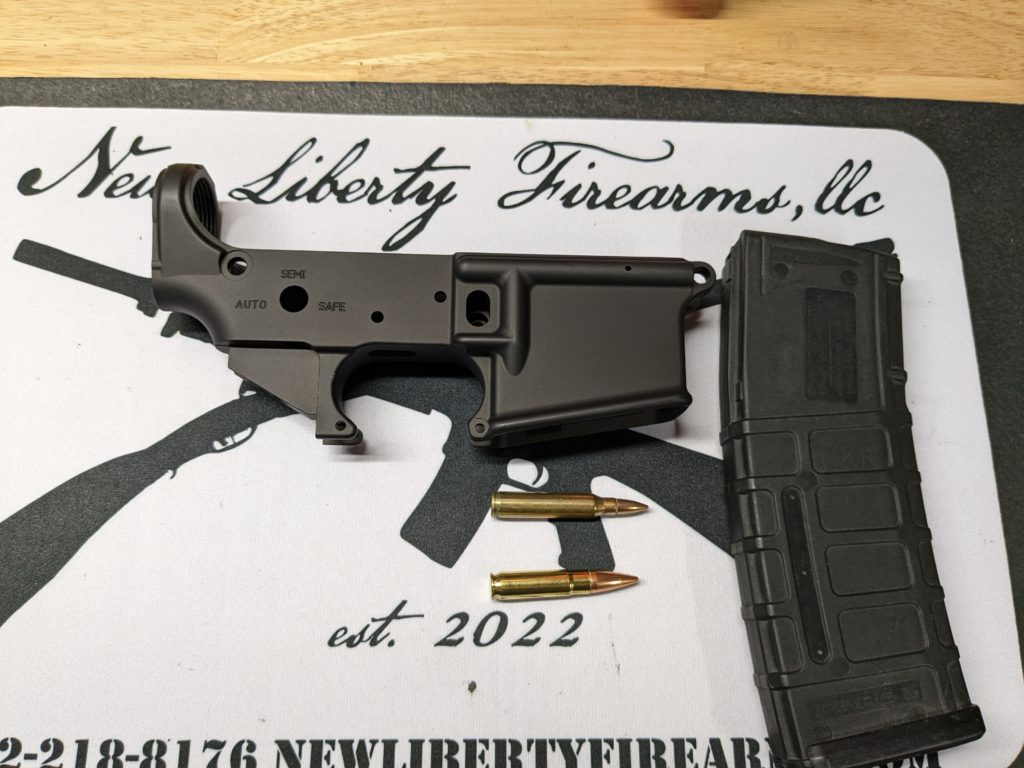

The AR-15 style receiver is the most common, and was the one that Armalite submitted to military trials chambered in .223/5.56 NATO, that eventually led to the M-16 family of rifles being adopted by the US Military. AR-15s are most often still chambered in .223/5.56 NATO (there is a difference between the chamberings, even though they share the same bullet diameter. This will be covered at a future point.) However, AR-15s are also commonly chambered in .300 AAC Blackout, .350 Legend, 6.5 Grendel, 6.8 SPC, .450 Bushmaster, .50 Beowulf, or numerous other calibers. The limiting factor for calibers to be used in an AR-15 is generally the overall length of a loaded cartridge, which must be short enough to fit into a standard sized AR-15 magazine. If the round is too long to fit into the magazine, they magazine can’t fit into the magwell, and the weapon will not be able to cycle.

There are applications where any of those rounds listed above, or others not listed, might be the rifle caliber for your AR-15 build. For instance, the ballistics of the .300 Blackout are such that the bullet starts dropping quickly after about 200 yards (depending on barrel length), so it wouldn’t be the best choice for a DMR style rifle meant to shoot long distances. However, from personal experience, I know I would rather have a .300 Blackout than 5.56 rifle for hunting tough animals like feral hogs at distances less than 200 yards. If you want a hunting rifle, and live in a state where you are restricted to straight walled cartridges, then .350 Legend or .450 Bushmaster would be options for you, depending on the kind of game you are hunting. If you mostly want something to have fun at the range with, then you will probably want lower cost ammunition, so something chambered in 5.56 would be a much better option than .450 Bushmaster. Even within the AR-15 family of potential calibers, there isn’t one caliber that will suit all the potential applications for a rifle. This is why we like to have a conversation with our customers when they are planning a build, in order to help guide the decision making process.

It is critically important to make sure that no matter what caliber you decide to go with for your build, that you shoot the correct ammunition for it. There are lots of instances of .300 Blackout rounds which were able to be chambered in a 5.56 NATO firearm. This usually leads to catastrophic results including destroyed firearms and physical injuries. The way to make sure you have the right ammunition is to check the roll marks on the barrel, which will indicate what the firearm is chambered in. Barrels can be swapped out on an AR-15 to a different caliber, so you should always check the barrel, not the markings on the receiver. Alternately, the receiver may say “Multi” for a caliber marking, that doesn’t mean the firearm can shoot multiple different chamberings without changing the barrel. If you are unsure what round your firearm is chambered in, seek assistance from a gunsmith, or someone else knowledgeable about firearms, to verify.

AR-10/LR-203:

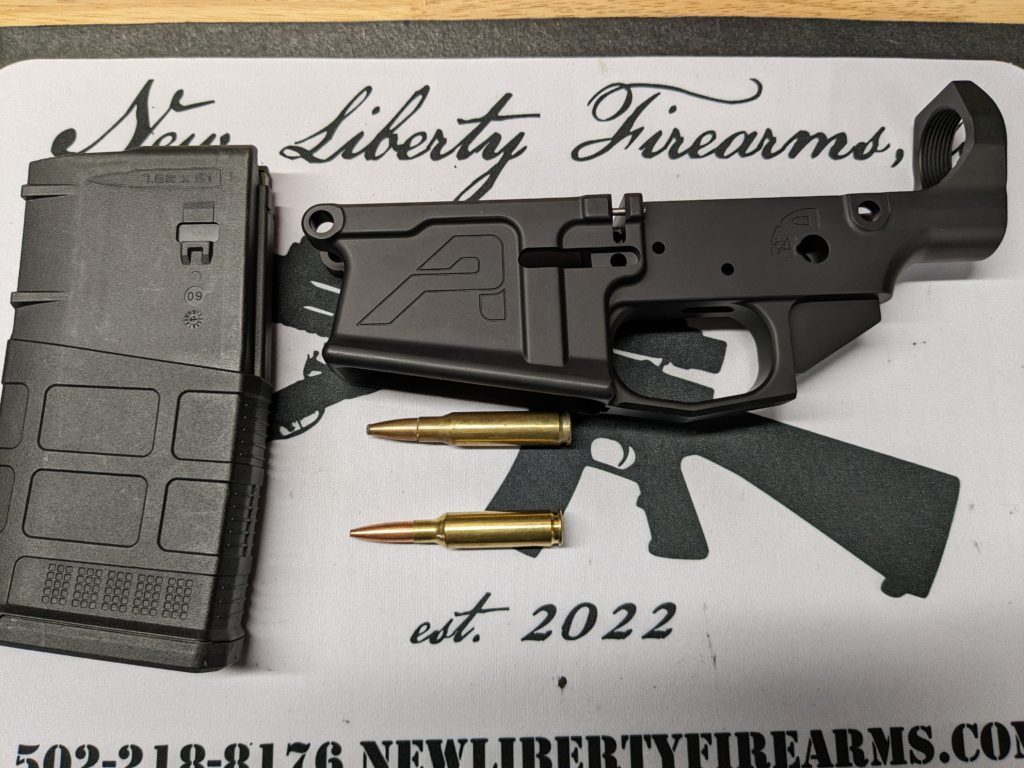

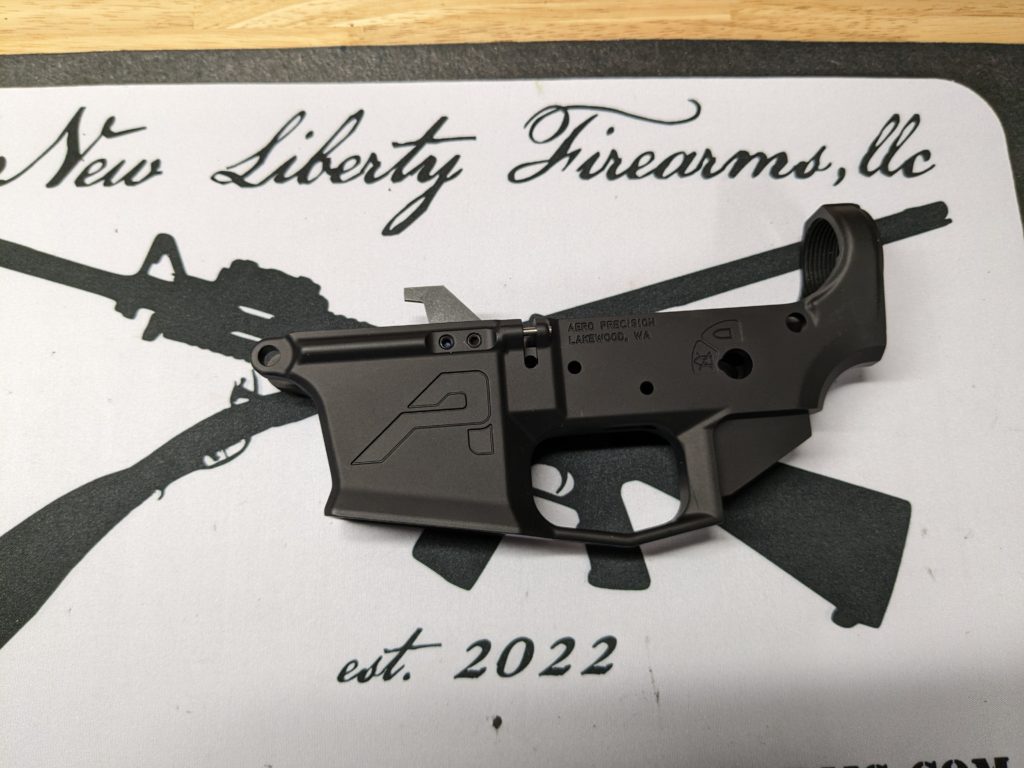

The next most common receiver format are the AR-10/LR-308 styles. It is important to note here that AR-15 receivers are almost all built to the military specifications for them, so they can generally all interchange with each other. However, there are two different formats for the this size, being the Armalite AR-10 format and the DPMS LR-308 format. They are not interchangeable, so you can’t run an Armalite lower with a DPMS upper and vice versa. To further add to the confusion, the LR-308 format is much more prevalent on the market, but people generally refer to them as an AR-10. So, it is important to match your upper with the lower for this rifle format, and we generally recommend getting the upper and lower from the same manufacturer. There are visual cues you can use to determine which style you have. For the sake of simplicity here, we will refer to this format as AR-10s here, for simplicities sake, but the same calibers apply to both Armalite AR-10 or LR-308 style receivers.

In terms of calibers, AR-10s offer the opportunity to “step up” to more powerful calibers than the AR-15 will allow. The original Armalite AR-10 was meant to compete with the M-14 in military trials, and was chambered in the standard infantry caliber of the time of .308 Winchester. .308 Winchester is still the most common caliber for an AR-10, but they can also be chambered in many of the other “short action” calibers. Short-action is a designation that ties into the bolt action realm, where cartridges/rifle actions are divided depending to the length of movement of the bolt, commonly being either “long action” or “short action.” Similar to the AR-15 calibers, which calibers can be chambered in an AR-10 depend on cartridge overall length, to be able to fit into the magazine. Aside from .308, other common calibers for an AR-10 would be .243 Winchester, 6.5 Creedmoor, .260 Remington, 7mm-08 or a few others. These calibers generally tend to be better suited to hunting large game at distance than AR-15 calibers, as the longer cartridge overall length allows for a higher case capacity for gunpowder in the loaded cartridge. Factors to consider in choosing a caliber are potential intended game for a hunting rifle, cost and availability of ammunition, and potential engagement distance and accuracy requirements at those distances.

There continue to be a large number of variables, but in general an AR-10 will be heavier and longer than an AR-15. Many AR-10s will also have heavier recoil, but that isn’t always true. An AR-10 in 6.5 Creedmoor will likely recoil less than an AR-15 in .450 Bushmaster. However, an AR-15 in 5.56 NATO will likely recoil less than an AR-10 in .308. However, if you are going to be hunting elk and want to us an AR style rifle, an AR-10 in .308 would be an appropriate choice while an AR-15 in 5.56 would not.

AR-9/AR-45:

The AR-9 and AR-45 formats have a number of similar traits, so for the purposes of this post I will treat them as one. Both of these are more modern formats, designed to be used with pistol calibers. The AR-9 is designed to use 9×19 Parabellum as a caliber, and the AR-45 is designed to use .45 ACP. They will often have a magwell designed to use popular pistol magazines, often but not always Glock pattern magazines. There are AR-9 or AR-45 lowers that use other magazine formats, so make sure you know what you are buying when you get one. Like AR-10s, there is less standardization of these formats than the AR-15, so it is a good idea to get your upper and lower from the same manufacturer to insure that they work well together.

Pistol calibers, in general, are going to be less powerful than rifle calibers, but there are still applications where they can be appropriate. Pistol caliber carbines (PCC’s), are commonly used in shooting competitions, because they are light and have low recoil. Ammunition for a 9mm is also currently less expensive than 5.56 at the time of writing, so it would be lower cost for a range gun, as long as distance is limited. There are also AR-9/AR-45 large format pistols which could be useful as defensive firearms. A pistol caliber carbine generally is not going to be appropriate for big game hunting though. So, there are times that it may be the right choice, and others where it may not.

Conclusion:

There are some parts that will be interchangeable between the formats above, but the critical parts of the firearm, like the receiver and barrel will be AR format specific, so deciding on what caliber you want your firearm to be in is a critical starting point in designing a rifle to suit your needs. The lower receiver is the serialized part that is legally considered the “firearm”, so choosing the one that is right for you is important before buying it. We realize that with the plethora of options on the market today, it can be confusing to know which parts you might need for your firearm. We welcome the opportunity to talk through what your needs are, and guide you in the right direction as you build the firearm of your dreams. Feel free to reach out to us through our contact page to start a conversation.